What we found

In the UK, women’s earnings drop sharply after childbirth—but the decline is significantly steeper if the first child is a girl. Over five years:

- Mothers of daughters see wages fall 26% more than fathers of daughters.

- Mothers of sons see wages fall only 3% more than fathers of sons

Daughters lead to more traditional household roles: more chores for mothers, less paid work, more traditional attitude to gender roles, and poorer mental health. We call this the daughter penalty.

Why does it matter

Our findings reveal how the gender of a first child can shape household dynamics and deepen gender inequality:

- Girls grow up seeing their mothers do more unpaid labour and stay home more

- The daughter penalty isn’t just about income – it is about values, expectations and the environments in which children grow up

- If, during the early and influential years of life, mothers of girls are less likely to work than mothers of boys, this may contribute to women (compared to men) coming on to the labour market with different exposures to the notion of a working mother and hence with different preferences over work and family.

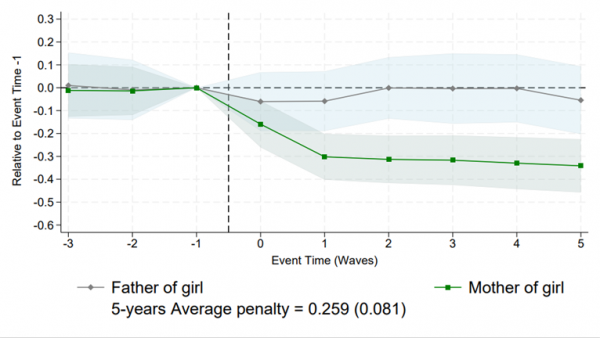

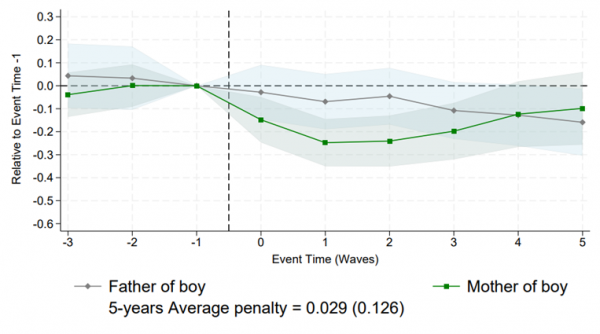

Figure 1 Earnings penalty comparison for mothers of boys and girls: mothers of girls face a much greater earnings drop than mothers of boys

How we studied it

Using longitudinal survey data from the UK (the UK Household Longitudinal Study), we investigate, for the first time, whether the gender of the first child influences the size of the child penalty.

We removed ethnic minority participants to avoid confounding due to cultural son preference, although our results are similar if we include these respondents. Our identification strategy is based on the assumption that the gender of the firstborn child is random conditional on the decision to have a child, to defend which we show balance on a rich set of predetermined characteristics between families with a firstborn son vs. a firstborn daughter.

We follow an established ‘event study’ method in which the effects of birth are inferred by comparing changes over time in wages for women who give birth with changes over time among similar women who have not yet given birth (with a similar approach taken for men). This allows us to reveal how gendered patterns in the home may emerge from the earliest stages of family life.

We looked at:

- Earnings, employment, hours worked

- Time spent on chores and childcare

- Mental health and relationship satisfaction

- Beliefs about gender roles and politics

We identify several consistent and significant differences for parents of daughters versus sons:

- Mothers of daughters experience a 26% earnings penalty over the five years after birth – compared to just 3% for mothers of sons

- Employment rates and working hours decline more sharply for mothers of girls than boys

- Mothers of daughters report doing a greater share of household chores alone and are more likely to be the main carer

- Mental health declines more steeply among mothers of daughters, while fathers of daughters report greater relationship satisfaction

- Attitudes to gender roles shift in a more traditional direction, especially among mothers of girls

What does this mean for policy makers?

We show that the child penalty is not gender-neutral: mothers of daughters face significantly larger earnings and employment losses than mothers of sons. We also document accompanying shifts in household production, gender attitudes, relationship satisfaction and parental mental health.

Having a daughter reinforces traditional gender roles in households – leading to a less equal division of labour and shaping early environments for children. Daughters grow up in more gender-regressive settings than sons, which could explain how gender gaps in work, values and career paths reproduce across generations.

Policy should act early. Support equal caregiving, normalise shared leave, and challenge stereotypes – especially within the home.

About this analysis

The study was funded by:

- ESRC Research Centre on Micro-Social Change (ES/S012486/1)

- ERC Advanced Grant Evidence-VAW (885698)

- ANID Millennium Institute IS130002

Bhalotra S., Clarke D. and Nazarova A. (2025). The Daughter Penalty. ISER Working Paper Series 2025-03.pdf

© MiSoC July 2025

DOI: 10.5526/misoc-2025-006