What we found out

Our study examines the primary predictors of political engagement among the children of immigrants, and demonstrates how these differ from the children of the UK born. First, our study corroborates existing research in the UK that shows that British-born parents who are more educated, who report higher levels of political interest, and who show up at the polls pass down these traits to their children: like many attitudes and behaviours, political engagement is socialised within families. Moreover, British-born parents and their adult children who live in areas with higher voter turnout generally are also more engaged themselves.

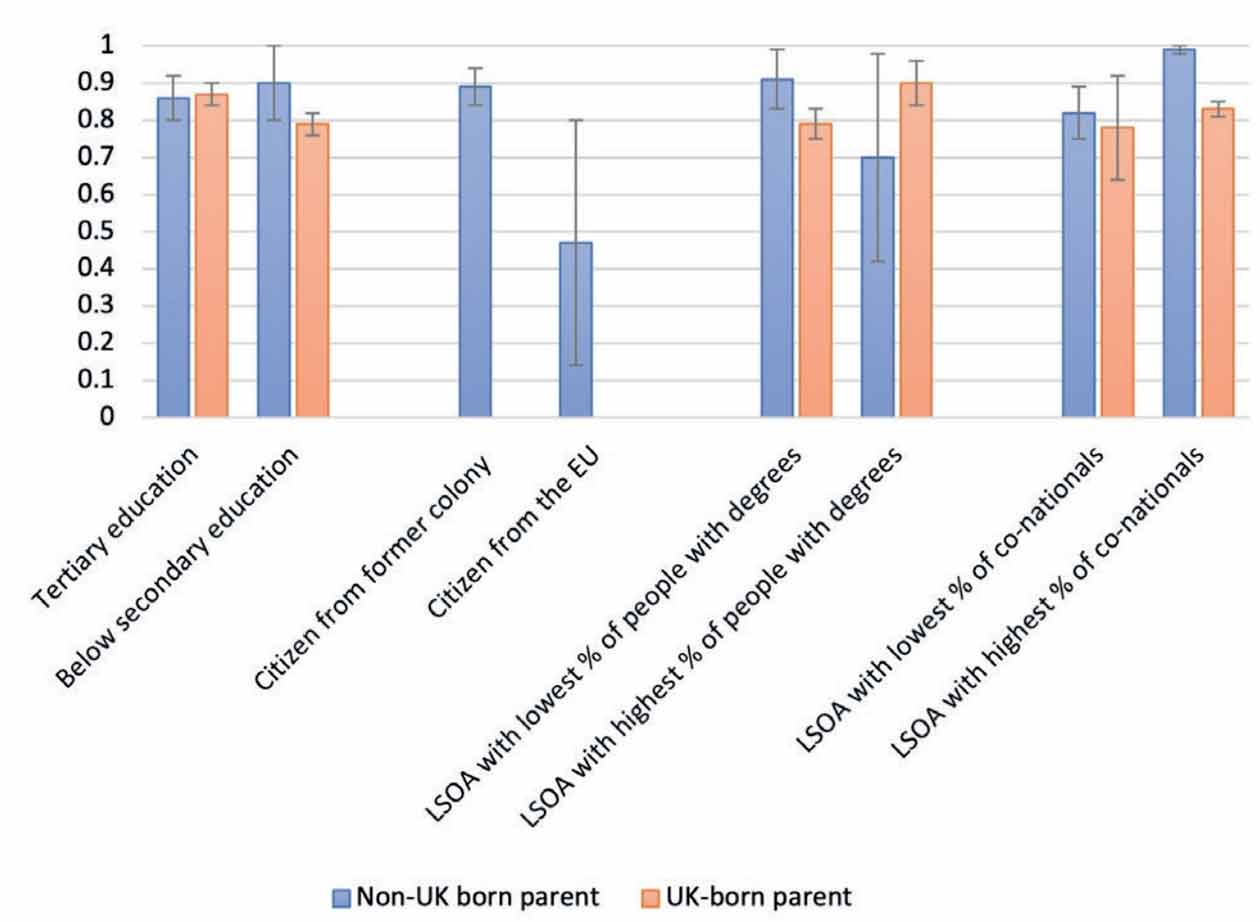

Our study is one of the first to demonstrate that the transmission of political engagement is different in immigrant families. In these families, parental education matters less – more highly educated immigrants show higher political interest but are not necessarily more likely to vote. Living in areas where voter turnout is high has no association with voting for immigrants, either. In contrast, the main predictors of voting for the foreign born is coming from a former colony, spending time in the UK and acquiring British citizenship, and living in areas with a

higher proportion of minorities.

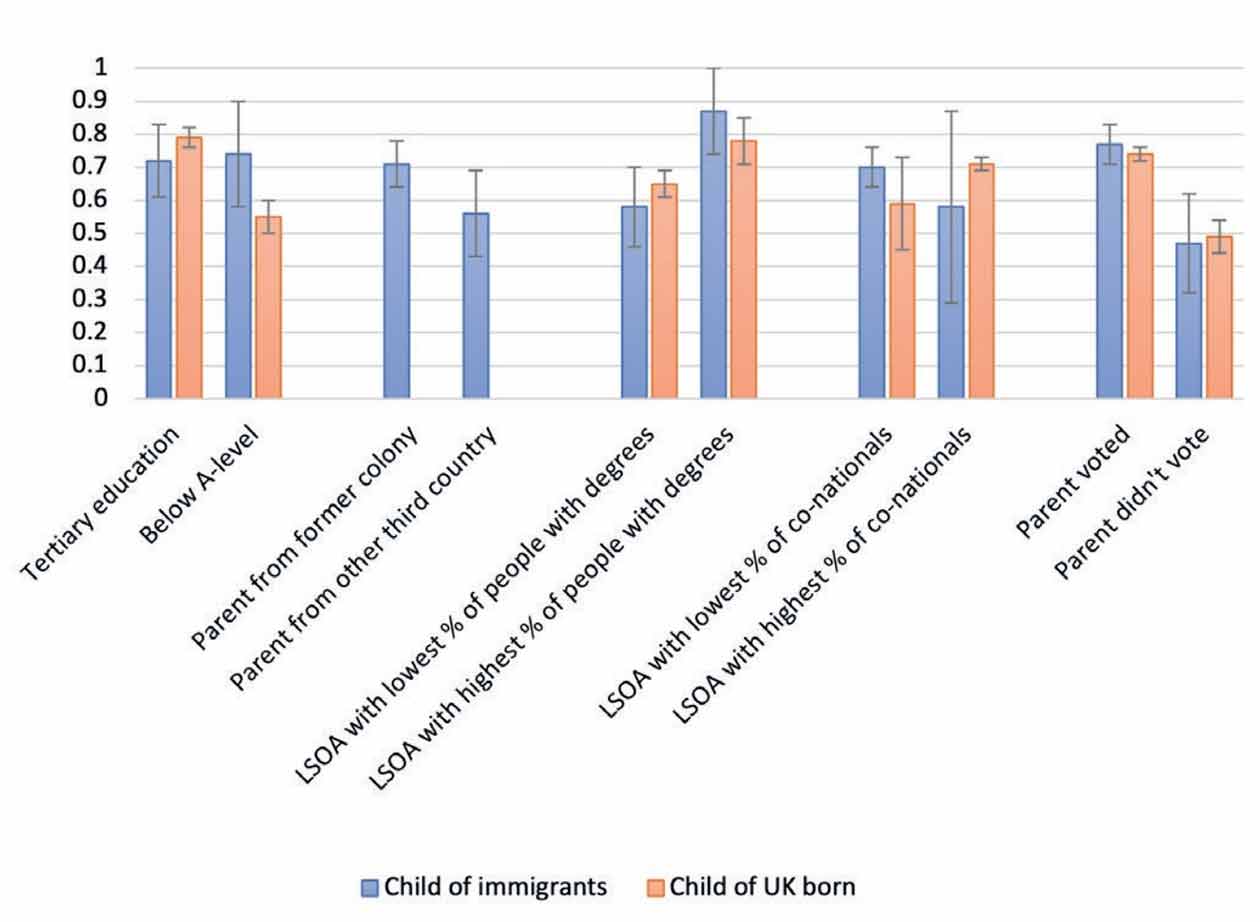

This pattern continues in the second generation: unlike the children of the British born, the children of lower educated immigrants do not differ from the children of more educated immigrants in their likelihood of voting. Nor do those with degrees themselves vote at higher rates than those with less education. Instead, having parent who comes from a former colony continues to be positively associated with voting, even though most of the second generation are birthright citizens who have been raised solely in the UK.

In some ways, however, the children of immigrants do look more like the children of the native born: they are much more likely to vote if their parents do, and they are more likely to show political interest and vote if they are surrounded by others who do so in their local community.

Why this is important

These findings are important for several reasons.

First, we show the intergenerational impact of afavourable pathway to political participation for thedescendants ofimmigrants coming from formercolonies. Commonwealth immigrants are immediately allowed to vote in Parliamentary and local elections if they have leave to enter or remain in the UK. This accelerated enfranchisement means that Commonwealth immigrants are actively courted by local political parties, have developed their own political organisations that incorporate newcomers, and are therefore incentivised to engage politically. This head start results in higher voting rates than immigrants from other parts of the world, which in turn increases the likelihood that their UK-born children will vote as well. If the British government wants to ensure the full participation of the growing foreign born and immigrant origin population, it should consider creating an expedited and lower cost pathway to enfranchisement for all immigrants that is more in line with that enjoyed by Commonwealth citizens.

Second, the fact that the children of less educated parents vote at lower rates in the UK is a failure of fair democratic representation. Our paper shows that this does not always have to be the case: for the children of immigrants, the link between parental and own education and political engagement is broken. We could stand to learn much by a closer examination of the differences in political opportunity and socialisation in immigrant and UK-born families.

Third, we show the importance of political modelling in the family, for the children of immigrants and the native born: having a parent who voted is a very strong predictor of voting for both. Efforts to increase voter turn out do not only matter for current democratic functioning, they will likely have lasting effects across generations as well.

How we found it out

Our study uses the first 11 years (2010/11 to 2019/20) of Understanding Society data – a nationally representative panel survey of around 40,000 UK households (or 100,000 individuals). Understanding Society provides a unique opportunity for the analysis of political socialisation processes of the second generation for three reasons. First, it includes a relatively large sample of immigrants and their descendants. Second, because interviews are

conducted with all adult members of the household, Understanding Society includes self-reported measures of political participation by both parents and their adult (16+) children, following them even after they leave their parent household. Third, the study includes detailed migration and naturalisation information that allows us to examine differences within the foreign-born population.

Next steps

Our study is one of the first to demonstrate differences the transmission of political interest and voting in immigrant and UK born families. In the future we plan to delve deeper in this data to understand differences in party preference and political alignment as well, to see whether transmission of more UK-specific allegiances are also transmitted differently among children of immigrants – and what this might mean for parties trying to capture their vote.

© MiSoC October 2022

DOI: 10.5526/misoc-2022-005