Teachers regularly assess students in educational settings, shaping students’ and parents’ beliefs about ability and influencing both student effort and parental support. In many contexts, teacher assessments also directly affect key educational transitions, for example in England where teachers’ grade predictions are used for university applications. Using pandemic-era data in which teacher assessments replaced exams, we investigated whether the use of teacher assessments advantaged or disadvantaged ethnic minority students relative to externally marked exams.

Learning from history – the pandemic experiment

English GCSE and A Level exams were cancelled in both 2020 and 2021 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2020, 95% of final GCSE grades received by students were the predicted grades assigned directly by teachers and schools, with the remaining five percent calculated through statistical modelling (Ofqual, 2020).

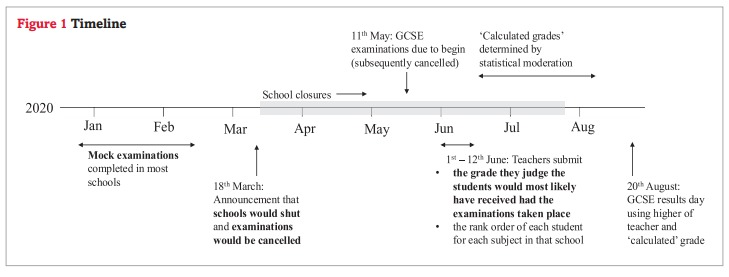

Figure 1 shows a timeline of how GCSE grades were assigned in 2020. In this research, we examined what these grade assignment processes meant for the attainment of ethnic minority students in England, at age 16. We used the National Pupil Database, which tracks students’ performance as they progress through school, and focused on the core subjects English and maths.

Main findings

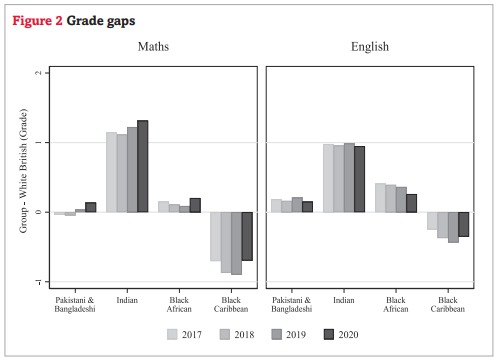

We found that, when teachers assigned GCSE grades in 2020, ethnic minority students did relatively better than White British students in maths and relatively worse than White British

students in English, compared to when the grades were from externally marked exams. Figure 2 shows that in 2020 ethnic minority students gained 10–20% of a grade relative to White British students in maths, but lost around 7% of a grade in English, compared to the previous year. We call these the 2020 ‘grade gap changes’.

We concluded that group- and subject-specific stereotyping is likely to have driven at least part of the ethnicity grade gap changes that we observed in 2020, when grades were assigned by teachers. However, first we checked whether those changes could be accounted for by any alternative explanations.

Explanations we ruled out

Could school closures have contributed to differences in grade assignment across groups?

School closures and exam cancellations were announced just two months before GCSE exams were due to begin (Figure 1), so teaching practices were largely unchanged across cohorts. Teachers were then instructed to base their predicted grades solely on students’ pre-closure work, and many actually stopped interacting with GCSE students altogether after school closures (Eivers et al., 2020). It is therefore unlikely that the 2020 grades reflect differences in teaching practices or school-closure experiences that differentially favoured students by ethnicity background.

Was this just a trend?

Accounting for time trends in GCSE maths and English grades since 2017 generally either increased the observed grade gap changes, or left them unchanged. The exceptions were Pakistani and Bangladeshi students in maths and Black African students in English, for whom the trends explained around 20% of the original grade gap changes. Overall, this indicated that the ethnicity grade gap changes in 2020 were not driven by time trends.

Were the cohorts just different?

We also tested whether the 2020 cohort composition differed from previous years, both overall and by ethnicity group. Our analysis showed that ethnic minority students in the 2020 cohort were predicted to perform slightly better than earlier cohorts in both maths and English, ruling out cohort differences as an explanation for improvements in one subject and declines in the other.

Was it ceiling effects?

Finally, as grades rose overall in 2020, grade gap changes might have mechanically reflected ceiling effects at grade 9 and the fact that some ethnicity groups had more ‘headroom’ for their grades to increase. However, our results held for both prior high- and low-attaining students, indicating that ceiling effects did not drive the findings.

One part of the puzzle

Given that no other explanation was able to entirely explain the grade gap changes that we observed, we concluded that group- and subject-specific stereotyping was likely to have

played a role in grades assigned by teachers for ethnic minority students in 2020. It is notable that both positive and negative stereotypes seem to have been at play.

However, we stop short of attributing the changes entirely to stereotyping for two reasons. First, stereotyped beliefs are unobservable in our data (as they often are for teachers themselves), and so it is not possible for us to directly relate any changes in outcomes between groups to teacher stereotyping. Second, a causal interpretation would rely on the assumption that changes in the levels or returns to unobserved student characteristics across groups would have affected grades in the same direction across subjects – an assumption that is plausible but untestable.

Policy implications

Overall, our results show that predicting students’ exam performance is a difficult task, as using predicted exam grades does seem to lead to grades that differ systematically from externally marked exam grades.

In particular, ethnic minority students in the 2020 GCSE cohort are likely to have received slightly higher grades in maths and lower grades in English than if their exams had never been cancelled. This may have had significant repercussions for the students of the 2020 cohort and their futures.

Policy responses to this work will depend on identifying the correct mechanism for the effects, but more information about how the attainment of different ethnic minority groups

changes throughout their schooling and across subjects could be helpful, as could revisiting exactly what form of assessment is most suitable for further and higher education admissions procedures more widely.

Other information

Cite this paper

Burn, H., Fumagalli, L., Rabe, B. (2024) Stereotyping and ethnicity gaps in teacher assigned grades. Labour Economics. Volume 89, August 2024, 102577.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2024.102577

Further information

- Dr Hester Burn, Research Fellow, UCL Institute of Education, h.burn@ucl.ac.uk

- Dr Laura Fumagalli, Research Fellow, ESRC Research Centre on Micro-Social Change, University of Essex, lfumag@essex.ac.uk

- Professor Birgitta Rabe, Professor of Economics, ESRC Research Centre on Micro-Social Change, University of Essex, brabe@essex.ac.uk

References

- Eivers, E., Worth, J., and Ghosh, A. (2020). Home learning during covid-19: Findings from the understanding society longitudinal study. Technical report, National Foundation for Educational Research.

- Ofqual (2020). Student-level equalities analyses for GCSE and A level: Summer 2020. Technical report, Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

© MiSoC December 2025

DOI: 10.5526/misoc-2025-011