Within the past year, most children in England missed up to 13 weeks of school in the first lockdown and another eight weeks in the most recent one. As the UK emerges from the latest mass school closure, evidence on the negative impact of the pandemic on the mental health of children and young people is mounting. But little is known about the specific role played by school closures in this deterioration.

New evidence shows that children who were out of school for longer during the first round of school closures in the spring and summer of 2020 experienced much greater declines in mental health than those who were able to return to school sooner. To the extent that we can compare them, the negative effects of school closures on children’s mental health seem to be even larger than the impact on their learning.

Like the effects on learning, however, it seems unlikely that the mental health declines will disappear without additional support. The government will also need to keep a close eye on whether policies designed to reduce learning loss will help or hinder attempts to restore children’s mental health.

What does the evidence tell us?

Children and young people have experienced enormous upheaval throughout the pandemic. As they return to school, there is widespread concern about the impact of school closures on children’s mental health and wellbeing. Yet these are sometimes discussed as though they compete with the government’s agenda to help children catch up academically.

Children’s mental wellbeing has been shown to be lower in 2020 than in previous years (Blanden et al, 2021; Waite et al, 2020; Raw et al, 2021). It has also declined as the pandemic has progressed (Newlove et al, 2021).

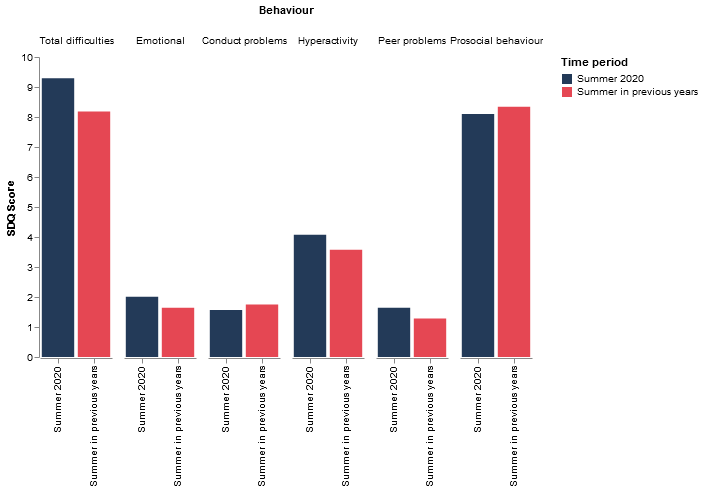

Figure 1 compares mothers’ reports on the ‘strengths and difficulties’ of their children in late July 2020 with information on children of the same age reported in previous summer holidays. In pre-pandemic years children were reported to have an average score of 8.2 for the negative behaviours and emotional difficulties in the index. This rose to 9.3 in late July 2020, an increase of 14% of the pre-pandemic average. But these results capture the overall impact of the disruption caused by the pandemic rather than the specific effect of school closures.

Figure 1: Overall change in Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire (SDQ) – summer 2020 compared with previous summers

Source: UK Household Longitudinal Survey, Blanden et al, 2021

Note: Prosocial behaviour is a ‘strength’, all other categories are ‘difficulties’

To understand how children’s mental health is affected by not being able to go to school, one can compare situations in which some cohorts of children were allowed to attend school while others were not.

This approach has been used in Japan, comparing pre-school children for whom nurseries were open with older children whose schools were closed. The study finds that compared with pre-schoolers, children affected by school closures experienced weight gain and their mothers reported more anxiety about their parenting (Takaku and Yokoyama, 2021).

We can make a similar comparison in England, using differences in the timing of the return to school after the first lockdown. Certain primary school year groups (Reception, Year 1 and Year 6 – those aged 4-5, 5-6 and 10-11) were prioritised for returning to school in June 2020. In other year groups, school attendance was often restricted to vulnerable children and the children of key workers.

Specifically, the changes in emotional and behavioural difficulties (a measure of children’s mental health) from pre-pandemic levels for children whose year groups were not priorities to return to school can be compared with those whose year groups were. Analysing data from the Covid-19 study of the UK Household Longitudinal Survey, it is possible to isolate the specific impact of school closures on children’s mental health (Blanden et al, 2021).

Negative behaviours were reported to have increased, driven by a rise in conduct problems (such as tantrums and disobedience) and hyperactivity. Comparing changes in children’s behaviour shows that those whose year groups were not priorities for school return have considerably higher ‘difficulties’ scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) than those who were in priority year groups.

The size of the effect is equivalent to a child newly exhibiting a particular negative behaviour (or experiencing an emotional difficulty) very often, or newly exhibiting two different negative behavioural or emotional difficulties some of the time (Blanden et al, 2021). The evidence suggests that these effects represent true changes in children’s wellbeing and are not driven by changes in the perceptions of emotions or behaviours by mothers.

The effects are large compared with the learning losses that children are estimated to have experienced as a result of the pandemic. A recent study has indicated that Year 2 children (those aged 6-7) in the autumn of 2021 were around two months behind 2017 expectations in maths and reading (Rose et al, 2021). Relative to average expectations, this is a smaller shift than that observed for children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties.

These children were in Year 1 during the summer term of 2020, so they were in priority year groups to return to school in June. Those who did return missed half a term of schooling (roughly six weeks) for which schools were closed in April and May. This is comparable to the maximum difference in schooling experienced by children in June and July in the study discussed above (Blanden et al, 2021).

These effects tell us about the difference in children’s wellbeing depending on whether they were in priority year groups to return to school during the summer term or not. But in reality, it is school attendance that counts. Because not everyone in priority year groups returned to school and some children in other year groups were able to attend, the effect of being in a non-priority year group is smaller than the impact of missing out on a full six weeks of school.

To calculate the effect of being out of school for longer, the estimates can be scaled by how different the attendance rates were between children in priority and non-priority year groups. Doing this suggests that missing six weeks of school could increase behavioural and emotional difficulties considerably – an effect roughly equivalent to children newly exhibiting three or four serious negative behaviours or emotional difficulties (Blanden et al, 2021).

To inform decisions about whether and how much support to provide children to overcome mental health challenges, it is crucial to understand how long the effects are likely to last.

Evidence shows that the difference in wellbeing between children who were and were not in priority year groups to return to school in the summer is of roughly similar magnitude at the end of September as it was at the end of July (Blanden et al, 2021).

What else do we need to know?

So far, the data can only show the effects of being out of school in June and early July on emotional and behavioural difficulties up until late September, when all children had been back at school for three to four weeks. If we were to apply these results to the school closures from which children in England are emerging in March 2021, they imply that children will still be struggling with the mental health effects until at least after Easter.

How much longer this might persist without additional intervention is unclear. The recent focus on children’s mental health might lead to the damage being addressed faster this time, but the results indicate that it is likely to take some time to mend the harm done.

It is also worth noting that what is reported here are the effects on average across all children in the year groups that were not priorities to return to school before the 2020 summer holidays. Their magnitude implies that there are likely to be some children for whom school closures lead to significantly more negative behaviours or emotions across several dimensions.

Owing to the relatively small number of children observed in the data, it is hard to pinpoint the characteristics of the children who are likely to be worst affected, but given its clear importance for policy targeting, more work is needed in this area.

As other Economics Observatory articles document, there is enormous concern about the learning losses caused by school closures, especially among disadvantaged children. The majority of parents believe that catch-up policies are necessary, but they are less supportive of longer school days and shorter holidays. This may be a result of their concern for their children’s mental health (Farquharson et al, 2021).

But we know that mental health and academic outcomes tend to vary together across the population (see Keilow et al, 2019, for Denmark). This means that children who are doing well academically also tend to be those with fewer behavioural problems.

Other work has highlighted the importance of children’s relative academic performance (how they compare to their classmates) in determining some aspects of mental wellbeing (Crawford et al, 2014). Policies to address learning losses and mental health may therefore reinforce each other.

Even if the opposite were true and additional pressure to catch up academically may reduce children’s wellbeing further, it is conceivable that these negative effects could be outweighed by the positive benefits of being back in a stable routine and seeing their friends.

It is also not clear whether the same children who have fallen behind the most academically are also those who have suffered the greatest deteriorations in mental health. Understanding more about the distribution of these different inequalities across the population, and whether plans to rectify one will narrow or widen the other, are important unanswered questions.

Where can I find out more?

- School closures and children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties: Report from the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) by Jo Blanden, Claire Crawford, Laura Fumagalli and Birgitta Rabe on the role of school closures in England on the emotional and behavioural wellbeing of children aged 5-11, as measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in the UK Household Longitudinal Study.

- Inequalities in responses to school closures over the course of the first COVID-19 lockdown: Study of school attendance during June and July 2020 from the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- The return to school and catch-up policies: Summary of a survey of papers just before children returned to school in March 2021, which contains information on parents’ support for catch-up policies.

- Best evidence on impact of Covid-19 on pupil attainment: A review by the Education Endowment Foundation of the early evidence on the size of learning losses among children.

- Children’s socio-emotional skills and the home environment during the COVID-19 crisis: Gloria Moroni, Cheti Nicoletti and Emma Tominey describe their work on how the home environment affects children’s socio-emotional skills.

Read the original article on the Economics Observatory website.