Even before the pandemic, many low paid workers faced insecure working conditions. Employment growth in the UK during the last decade skewed towards atypical roles such as self-employment, zero-hours contracts and agency work. These types of jobs guarantee no or only a low level of earnings.

Workers can face large week-to-week changes in the hours they work. Most importantly, they face significant uncertainty over their short-term income and time commitments.

But are these jobs bad for workers? Psychological research suggests that uncertainty often triggers anxiety and stress and that the vast majority of people try to avoid it.

Existing research also shows that higher income instability is associated with an increased risk of depression, poorer health, indebtedness, food insecurity and behavioural problems in adolescents and children.

It has sometimes been claimed that workers in atypical and unstable jobs ‘prefer’ this type of working arrangement, because it gives them freedom to combine work with other commitments such as education, training or care.

This view is sometimes supported by surveys that show workers in atypical jobs express higher job satisfaction, and only a minority say they would like more hours. In contrast, in-depth interviews with workers in atypical roles have shown that the work related instability they face can cast a long shadow over their lives, from making it harder to manage their finances to straining their family relationships.

How should we interpret these results? Asking workers directly about their work related choices and preferences can be problematic. When answering survey questions, workers will be influenced by other characteristics of their job such as pay, distance from home, schedules and so on. They will also be influenced by the wider local economic environment and the availability of good jobs. A zero-hours worker expressing satisfaction with their job might simply be reflecting lack of better alternatives.

Experimental methods can get around these problems. Funded by the Nuffield Foundation and the Economic and Social Research Council, I conducted an experimental study aimed at examining workers’ reactions to uncertainty about work availability and associated pay. 301 working age, low income, UK residents took part. Participants were randomly assigned to three groups (two treatment groups and a control group) and asked to choose between completing a work task-transcribing Latin text for pay, and receiving a lower benefit. In the control group, work was always available. In the two treatment groups, work availability was determined by a coin flip after the participant made their choice. Comparing participant choices across groups gives us an insight into how workers react to uncertainty.

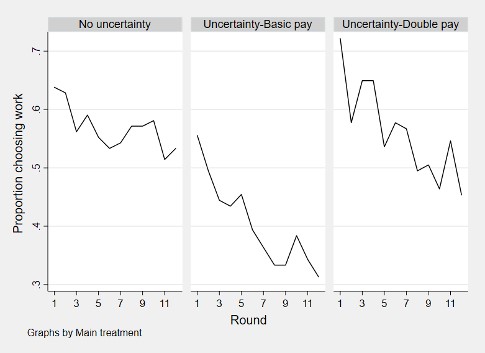

Figure 1: Proportion choosing to work by round and treatment group

Far from preferring it, workers avoided uncertainty whenever they could. Participants facing uncertain work availability were 15 to 30 percentage points less likely to choose to work compared to participants who faced no uncertainty (see Figure 1). The more participants became familiar with the choice they faced, the larger the differences between groups. Even when they were offered a pay rate that was twice as high, participants ended up choosing to work less often. The results suggest uncertainty is a burden for workers and contradict the view they willingly choose unstable jobs.

Public policies can limit hours and pay instability. Employers could be mandated to offer workers a contract that reflects their regular working hours rather than a minimum. Limits on short-term scheduling and re-scheduling, as well as compensation for shifts cancelled at short notice would similarly help.

The Government could also mandate a higher minimum pay whenever hours vary in the short-term. Finally, the welfare system can support workers in unstable jobs by promptly topping up their pay when work is unavailable. At the moment, arrears in Universal Credit payments amplify swings in income.

There is a danger that the economic crisis brought on by the coronavirus pandemic will accelerate the growth of unstable and insecure employment, as the last crisis did.

To limit job losses and support employment growth, the Government may be reluctant to limit labour market flexibility in any way. My research suggests that such an approach would be misguided. There is no evidence that more flexibility always leads to more employment. In fact, there is no evidence that the increase of jobs with unstable hours and pay helped reduce unemployment in the last decade, perhaps because the UK labour market was already quite flexible before this increase.

After nearly two decades of persistently high levels of low pay, the UK has been very successful in using a higher minimum wage to reverse the trend without affecting employment.

In the same way, policy interventions geared towards limiting pay instability could support workers without harming the labour market.