The ESRC Research Centre on Micro-Social Change (MiSoC) has published a new Explainer outlining the findings of new research. We find as automation reshapes the labour market, hard-to-automate sectors will see rising wages – but employment growth in some of these sectors will remain constrained. Workers in declining sectors often cannot easily move into expanding fields.

The research

Automation is transforming the labour market, reducing demand for workers in manufacturing and routine occupations while increasing relative demand for healthcare, education, and other hard-to-automate sectors. But what happens next? Will displaced workers flow into growing sectors, or will adjustment take other forms? With AI poised to accelerate these shifts, the answers have never mattered more.

We employ an economic model that accounts for how easily workers can move between different occupations. Using German labour market data spanning several decades, we estimate how responsive employment in each occupation is to wage changes – crucially taking into account the extent to which shocks are correlated across occupations that are closely related.

We validate our approach against historical data from 1985–2010, confirming that our framework helps explain past patterns of wage and employment change. We then apply expert assessments of automation risk to project future labour market adjustments.

Findings

Some occupations respond to wage changes much more than others. Healthcare and education occupations are particularly unresponsive – even substantial wage increases produce only modest employment growth. These sectors require specific qualifications, lengthy training, and often vocational commitment that limits how quickly the workforce can expand.

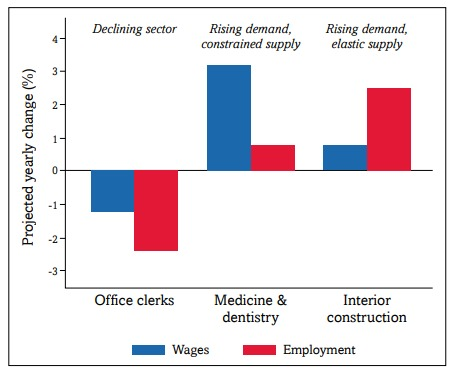

Automation will increase wages in hard-to-automate sectors, but employment won’t follow. Our projections show that healthcare and education – the sectors least exposed to automation – will experience rising wages as demand shifts towards them. But because these occupations are unresponsive to wage changes, this translates primarily into higher pay for existing workers rather than significant job creation.

Figure 1 Projected automation impacts on wages and employment for three example occupations (Three example occupations out of 126 studied)

Workers in declining sectors often face limited escape routes. When automation reduces demand in one occupation, similar occupations are often affected simultaneously. Manufacturing workers, for example, find that related jobs are also declining, leaving few viable transition options. This amplifies downward wage pressure in affected sectors. Crucially, our model identifies which job transitions are realistic based on observed worker flows – not just which sectors are expanding.

What does this mean for policy makers?

Understanding whether sectors adjust through wages or employment matters for policy design. Effective policy must look beyond which jobs are at risk to ask: can workers in these jobs realistically transition elsewhere? Which growing sectors can actually absorb displaced workers.

If automation pushes up wages in healthcare and education but employment doesn’t follow, the constraint isn’t pay – it’s the supply of qualified workers. Addressing emerging shortages in these sectors requires direct investment in training pipelines: expanding places on nursing and teaching courses, reducing barriers to qualification, and creating accessible retraining routes for workers from other sectors.

For workers in declining occupations, traditional advice to ‘retrain for growing sectors’ may be unrealistic if those sectors have high entry barriers. Policy may also need to consider supporting workers who cannot easily transition – through place-based interventions or wage subsidies in affected communities.

Our analysis focuses on one important mechanism – how workers move between occupations in response to wage changes – among the many ways technological change affects the labour market. Other factors, including job quality, working conditions, and the emergence of entirely new occupations, also shape outcomes. But understanding occupational mobility is crucial for designing effective responses to ongoing technological change.

About the authors

Dr Michael J. Böhm is Professor at TU Dortmund..

Dr Ben Etheridge is Senior Lecturer at the University of Essex.

Dr Aitor Irastorza-Fadrique is Post-Doctoral Fellow at University of the Basque Country.

Further information

Full paper

Böhm, M.J., Etheridge, B., Irastorza-Fadrique, A. (2025), The Impact of Labour Demand Shocks when Occupational Labour Supplies are Heterogeneous.

Cite

Böhm, M.J., Etheridge, B., Irastorza-Fadrique, A. (2025), Why displaced workers won’t easily fill healthcare and education shortages. MiSoC Explainer, University of Essex. DOI: to follow

Further information

For further information about this research, please contact Louise Cullen, Head of Communications and Engagement at the Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex, at lcullen@essex.ac.uk