COVID-19 has turned the lives of millions of parents and children upside down. As a migrant and single mother with a full-time academic job, I have found the lockdown and the school closure particularly demanding. Of course, I am not alone. Emerging research shows the lockdown will have far-reaching consequences, especially for vulnerable families. Here I will review research conducted by others on the disparities the school closures have been producing; I will identify gaps for future research and make policy recommendations about reopening the schools.

Investing in education will pay off

Schools are supposed to foster talent, skills, and cognitive competence. They are also supposed to transfer knowledge. State schools safeguard equal opportunities in the labour market and beyond, making them the engine of social mobility. However, in these unprecedented times, schools cannot function normally.

We do not yet know whether the transfer of schooling to parents during the lockdown increased the impact of parental resources (or lack of resources) on pupils’ educational outcomes. But we can be sure that this question will occupy researchers in the years to come. We have also limited understanding of how families are coping with their home-schooling obligations. There is a growing concern that, absent swift action, schools will not be able to close the gap in learning that disadvantaged pupils from migrant and ethnic minority groups and those with less-educated and single parents.

School interruption drops academic performance

Previous research suggests an interruption of 12 weeks in schooling will drop test scores significantly. This loss in learning will be unevenly distributed. School closure might even advance learning of children from better-off families. Well-positioned parents can teach their children, and they can afford online tutoring: The Institute for Fiscal Studies has conducted the only large-scale homeschooling study in the UK to date. It compares time spent on ‘educational activities’ across groups of children, and the results are stark. The richest primary school children spend on average six hours per day on educational activities, and secondary school kids spend five and a half hours per day. This is exceptionally high, and these children’s learning may not be disrupted immensely.

In contrast, pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds have less space to do their schoolwork at home. Worse yet, some lack IT facilities altogether; or, if they have them, they share with siblings or parents. Parents also struggle with limited time and feel unable to help or have a limited understanding of the material school has provided. This widens the gap in academic performance between children from disadvantaged backgrounds and their privileged peers.

The IFS analysis shows that overall “children from better-off families are spending 30% more time on home learning than are those from poorer families.” The true figure may well be much higher still. The IFS study excludes the hardest-hit parents with no computer or internet connection, and those with a migration background who are not fluent in English. The poorest families in this research are by far the poorest in the UK.

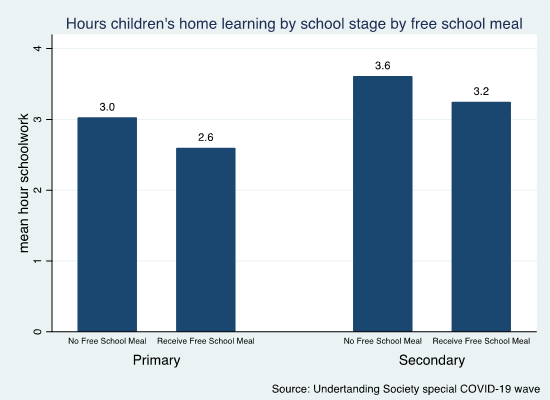

No study gives a complete understanding about the true level of disadvantages school interruption have been generating for the poorest children and those with ethnic backgrounds. Sait Bayrakdar and I currently analyse the nationally representative Understanding Society COVID-19 dataset, which includes a sample of respondents with an ethnic minority background. Our findings show that children who receive free school meals spend on average significantly less hours on home learning than their peers: on average 2.6 hours a day those in primary and 3.2 hours a day those in secondary school as opposed to children who do not received free school meals spending 3 and 3.6 hours, respectively.

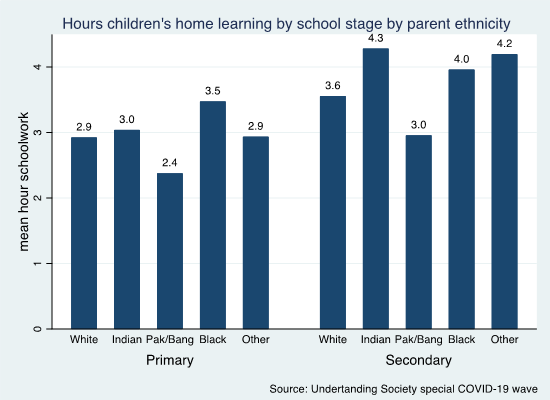

Children with Pakistani and Bangladeshi background spend substantially less time on home learning in primary (2.4 hours a day) and secondary school (3 hours) than all their other peers. Children with Black-Caribbean or Black-African background in secondary school spend the highest number of hours (4.3 hours a day) on home learning during the schools closure in the UK.

However, children will start, some already did, school before research of this kind can provide a good understanding about the consequences of school interruption. Therefore, education policies should not wait until representative research uncovers the true negative scarring impact of homeschooling but act promptly and protect the hardest hit children.

Policy recommendations

Dedicated education policies will be necessary to close the education gap. First and foremost, schools should open first for children from disadvantaged families. Schools in wealthier neighbourhoods, independent and private schools will be better prepared to reopen. Schools in deprived areas will have fewer resources and staffing to mitigate health risks and start so soon. In such cases, the government and local authorities should invest in minimising the damage of the lockdown on the most vulnerable groups in these areas. They should work to make these schools safe so that children can return. Resuming school while also ensuring safety should occur first with children who are eligible for school meals and/or who are in single parent or migrant families.

Staggered resumption of school based on targeted need will not be enough to close the education gap. Schooling should continue a few days a week during the summer holiday period, especially as families are unlikely to go on holidays this year. Keeping schools open on Saturdays in the new academic year will also mitigate the educational disadvantages.

A final suggestion is volunteerism. Despite my advanced education (a doctorate), I struggle to home-school my daughter in English — spelling in particular is a challenge. Luckily, a colleague and friend offered to hold Zoom meetings with her every day. This improved her academic skills, and gave her something to look forward to after the abrupt disconnection from her friends, school and outdoors activities. Personal experience has taught me that a volunteer network that provides free online courses for children who are hardest hit would have multiple benefits.

Read the original article on the LSE website here.