Across Europe there has been a rise in political parties focussing on an ethnic conception of a nation, explicitly opposed to immigrants and minorities and their claims to belonging. Publicly articulated concerns about the ‘failures’ of multiculturalism and integration have led to claims about a lack of minority endorsement of national identity and a rise in populist conceptions of what a nation is. But what evidence is there on the relationship between people’s political and ethnic identities? Are the UK’s (ethnic) minority and majority different in this respect?

We used data from the UK Household Longitudinal Survey (Understanding Society) on a broad range of questions about their lives including about respondents’ personal identities across different domains, which enabled us to answer these questions.

The first thing that was clear from the analysis was that for most people their political and ethnic identities are not their main personal identity. For both majority and minority groups other sources of identity, such as age or life stage, gender, family, education and profession are more important.

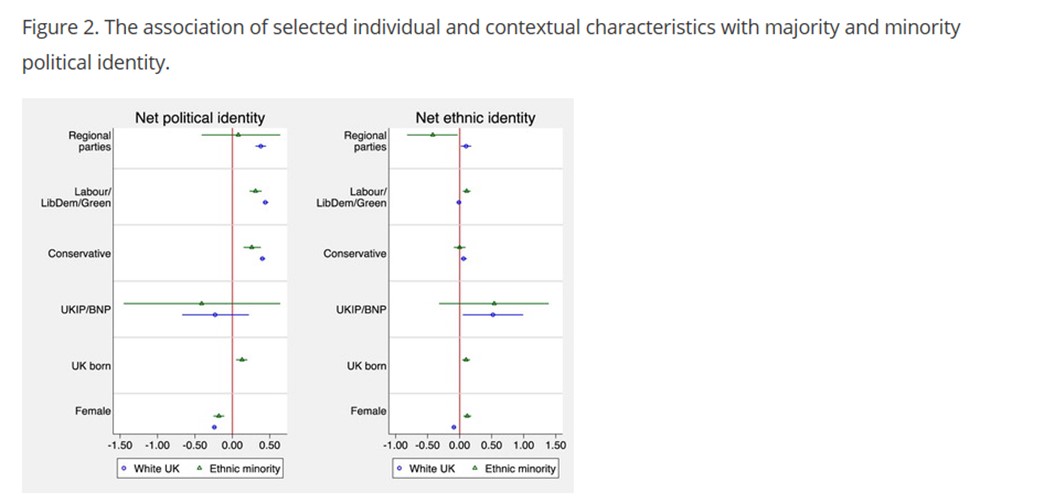

This research found that most characteristics that are associated with stronger political identity are also associated with stronger ethnic identity and these are the same for both the majority and minority groups. One exception was that majority group women reported weaker ethnic identities than men while the opposite was true of minorities.

We merged this data with the 2010 General Election results to measure the UKIP and BNP presence in the neighbourhood, and found it is associated with stronger ethnic, but not political identity, particularly among the majority. This suggests that the political messaging around ‘in groups’ and ‘outgroups’ propagated by these political parties may have led to a greater sense of awareness of ethnic identity, particularly among the majority.

For minorities, experiencing ethnic or racial harassment or being Muslim is associated with a stronger political but not a stronger ethnic identity. And the second generation, that is, ethnic minorities who were born in the UK, report stronger ethnic and political identities than the first generation.

Some contextual factors, such as political mobilisation around issues of immigration, that might be expected to influence both these identities are difficult to measure in large surveys, and was not asked in this one. Instead, we asked if, after accounting for the measured characteristics discussed above, the strength of the two identities was correlated. The answer is yes. And this correlation is stronger among the majority than the minority, and within the majority among those with affiliation to the Conservative party, or those with no party affiliation, and among those with less egalitarian beliefs.

In the past, research into ethnic identity has suggested that minorities place the most significance on their ethnicity. This research suggests that this is not the case – minorities, just like the majority, are more heavily invested in other aspects of their identity, such as their education, work or family life. The highly politicised public narrative around Muslims in particular being more invested in ethnic identity and self-segregation than other groups is also undermined by this research. Instead, it shows Muslims expressing their political identity, perhaps reflecting a more general politicisation of ethnicity. Against a backdrop of studies which have shown a decline in ethnic identity across the generations, this research suggests second generation minority groups are continuing to identify themselves by their ethnicity, but also becoming more politically invested than their parents.

Key points:

- Political and ethnic identities are less important to majority and minority groups than other identity domains, such as life-stage, work or education.

- Political and ethnic identities are stronger among second generation minorities.

- Having experienced harassment was significantly associated with a stronger political identity, but not an ethnic one.

- There is evidence of co-evolution of political and ethnic identities, more so among the majority and among them for those with affiliation to the Conservative party or who have less egalitarian values.

Alita Nandi & Lucinda Platt (2018): The relationship between political and ethnic identity among UK ethnic minority and majority populations, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies

A version of this was published in Understanding Society’s Insights 2020.