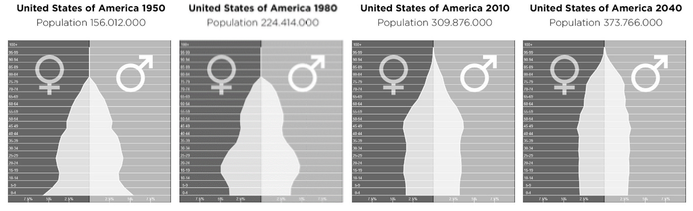

As the baby boom generation now reaches retirement age, concerns regarding the sustainability of our pension and health care systems are mounting. Understanding the origins of this phenomenon is therefore crucial to help us forecast future demographic changes and design more adapted public policies. In Figure 1, we follow the evolution of the age structure of the US population from the birth of the baby boom generation circa 1950, to its passing circa 2040.

Figure 1: Age structure of the US population, 1950-2040

Source: United Nations

Several different theories have been put forward by demographers, sociologists, and economists to explain the sudden rise in birth rates that occurred between the early 1940s and the late 1960s. Yet no consensus has emerged in the scientific community.

The most popular narratives in the general public mention the return of mobilised soldiers or the wave of optimism after the end of the war as responsible mechanisms. However, the data show that the baby boom was not only the result of a catch-up of pregnancies averted during the war, nor was it limited to countries involved in WWII, casting doubt on these explanations alone.

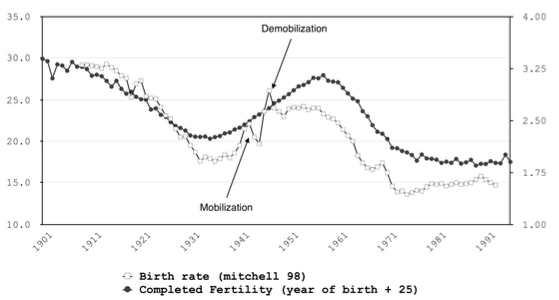

Figure 2 compares two indicators of fertility: the birth rate, which reports the number of births per 1000 people in the population in a given year, and the completed fertility rate, which represents the total number of children that women born in a given year had over their lifetime. War mobilisations and demobilisations have only had a ‘tempo’ effect – births were averted for a few years, but caught up later on. They cannot account for the deeper cycle in completed fertility that started in the early 1930s.

The earliest theory of the baby boom in the social sciences was proposed by Easterlin in 1966. He suggested that generations entering adulthood upon favourable economic conditions relative to those that prevailed in their childhood, were more inclined to have larger families. Although appealing, this theory is not confirmed by the data (Hill 2015).

Figure 2: Birth rates versus completed fertility

Sources: US Census and Current Population Survey

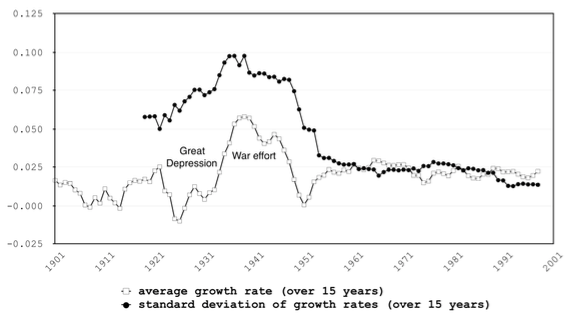

Figure 3: Average and standard deviation of income growth rates

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Fishback and Kachanovskaya (2015)

How much do children cost?

Economists have focused their attention on factors that influence the cost of having children to explain fluctuations in fertility. In particular, having children requires a substantial time investment. In a context in which mothers are expected to make a large part of that investment, the monetary value of their time, also called opportunity cost, may be seen as the main driver of fertility decisions. Some scholars have highlighted that this cost was particularly low for women who gave birth to the baby boom generation. Two main reasons have been put forward to explain why the value of women’s time has potentially declined during the baby boom.

First, many women entered the labour force during the Great Depression and war times. This movement negatively affected the demand for female labour right after the war. Hence, the young women of the time faced scarce labour market opportunities (Doepke et al. 2015, Bellou and Cardia 2014). The choice of a career over a family seemed therefore less desirable. However, the fluctuations in female labour force participation in that period were of a magnitude that can hardly explain the massive spike in fertility that the baby boom has been.

Second, the years of the baby boom were marked by a technological boom that affected the ‘home production’ sector, through the dissemination of electrical appliances such as the washing machine or the dishwasher. This sudden increase in efficiency in household chores would have freed up time for housewives to take care of larger families (Greenwood et al. 2005). This theory, though, has been challenged on two grounds. First, data on electrification reveal a negative impact of the diffusion of home appliances on fertility, rather than the contrary. Second, the Amish community, which barely uses modern technology, has also experienced a coincidental baby boom (Bailey and Collins 2011).

A third theory has focused on the cost of housing. The period of the baby boom has indeed been marked, particularly in the US, by a movement of suburbanisation, facilitated by the drop in the cost of cars as well as the development of highways. Again, data on the evolution of rents over time allow us to discard this mechanism as an important driver of the baby boom (Murphy et al. 2008).

How much risk do children involve?

What if, instead of (or in parallel to) the cost, it was the risk associated to having children that has evolved over time?

One risk that has declined sharply during the period of the baby boom is that of mothers dying during labour. Data for the US confirm that states where we observed the largest drops in maternal mortality rates also experienced the largest spikes in birth rates (Albanesi and Olivetti 2014). But, can that be the whole story?

In a new study (Chabé-Ferret and Gobbi 2018), we suggest that having children is perceived to be riskier, and therefore is averted, in periods of high economic uncertainty. Indeed, children require an uninterrupted flow of attention, which is difficult to commit to when economic conditions vary too frequently. On the one hand, they involve financial expenses that are extremely hard to cut in times of hardship. On the other hand, they also need an investment in terms of parental time that may prove very costly if employment prospects suddenly improve (de la Croix and Pommeret 2019).

While there has been a huge controversy regarding whether fertility responds positively or negatively to economic booms and downturns, most researchers have found that uncertainty about future economic conditions tended to delay childbearing. Indeed, risk-averse individuals choose to postpone commitments during economic turbulence (both ups and downs) in the hope of more stable tomorrows. Ultimately, a prolonged enough period of high economic uncertainty can not only delay childbearing, but can even reduce the total number of children a woman has over her lifetime.

Using historical data from the US Census, the authors show that the total number of children a woman has is strongly and negatively associated with the volatility of economic conditions this woman faces in her twenties and early thirties. They estimate that variations in economic uncertainty may explain as much as 60% of the one child difference in fertility between the trough and the peak of the baby boom.

The Great Depression and WWII represent a massive surge in economic uncertainty by historical standards, while the post WWII-period has been an epoch of stable economic growth. Hence, we conclude that the post-war baby boom should be regarded at least as much as a pre-war baby bust.

In the absence of modern contraceptives, the main channel through which economic uncertainty depressed fertility is the age at marriage. Indeed, the most affected women married on average two and half years later than subsequent cohorts. Also, a larger share of women eventually never married.

Economic uncertainty depressed fertility across all segments of the population, though substantially more in some categories. For instance, African American women were 50% more affected than their non-Hispanic White counterparts, consistent with previous research showing that ethnic minorities suffer more from business cycle fluctuations. Women with high school education were found to be more impacted than both less, and more educated women. Women residing in more developed areas also show greater sensitivity to economic uncertainty.

Will we face a new baby boom again?

Interestingly, the fertility rate of cohorts born after 1945 seems much less affected, if at all, by economic uncertainty. We suggest several factors may have loosened the relationship between economic uncertainty and fertility – first, the extension of the fertile window, but also the appearance of instruments to smooth the effect of economic fluctuations, such as the development of the financial sector or the implementation of various types of safety nets (unemployment benefit, poverty relief programmes, universal health coverage, etc.)

This could have important implications for the current discussion about the impact of the Great Recession on fertility rates. Indeed, birth rates have shown a sharp decline in the US since 2008. However, women now have more flexibility to delay and catch up when conditions are more favourable.

References

Bailey, M J, and W J Collins (2011), “Did improvements in household technology cause the baby boom? Evidence from electrification, appliance diffusion, and the Amish”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 189-217.

Bellou, A, and E Cardia (2014), “Baby-boom, baby-bust and the Great Depression”, Unpublished manuscript.

Chabe-Ferret, B, and P E Gobbi (2018), “Economic Uncertainty and Fertility Cycles: The Case of the Post-WWII Baby Boom” CEPR Discussion Paper 13374.

de la Croix, D, and A Pommeret (2019), “Childbearing postponement, its option value, and the biological clock”, CEPR Discussion Paper 12884.

Doepke, M, M Hazan, and Y D Maoz (2015), “The baby boom and World War II: A macroeconomic analysis”, The Review of Economic Studies 82(3): 1031-1073.

Easterlin, R A (1966), “On the relation of economic factors to recent and projected fertility changes”, Demography 3(1): 131-153.

Greenwood, J, A Seshadri, and G Vandenbroucke (2005), “The baby boom and baby bust”, American Economic Review 95(1): 183-207.

Hill, M J (2015), “Easterlin revisited: Relative income and the baby boom”, Explorations in Economic History 56: 71-85.

Murphy, K M, C Simon, and R Tamura (2008), “Fertility decline, baby boom, and economic growth”, Journal of Human Capital 2(3): 262-302.

Read the blog post on VoxEU here & the CEPR discussion paper here.