In a recent book, The Welfare Trait, Adam Perkins argues both that exposure to childhood disadvantage damages personality development, and that the welfare state is causing more children to be born into disadvantaged households; the combination of these two effects means, Perkins argues, that the welfare state itself is directly increasing, in the long-run, the number of individuals whose personality is leading them to be work shy.

To quantify the likely size of these effects, Perkins cites our research (Mike Brewer, Anita Ratcliffe and Sarah Smith, 2012, “Does welfare reform affect fertility? Evidence from the UK”, Journal of Population Economics, 25(1), pp 245-266, DOI: 10.1007/s00148-010-0332-x, and available free at

http://0-www.jstor.org.serlib0.essex.ac.uk/stable/pdf/41408911.pdf on the effects on fertility of an increase in government support for families with children. Our paper showed that the expansion in government support for low-income households with children that occurred in the first few years of the Labour government (we looked at the period from 1999 to 2003) increased the number of births to women living with a partner who were particularly affected by the reforms by virtue of living in low- to middle-income families.

Our work is cited by Perkins in the following way: “Government figures show that approximately 800,000 children were born in the UK in the last year, about 110,000 of them into workless households. Had the previous 15 years not seen a 50 per cent increase in welfare generosity, that latter total would have been approximately 15 per cent smaller (about 14,000 fewer children per year; Brewer et al., 2011).”

Although our results clearly show that the reforms to benefits and tax credits for families with children in the late 1990s and early 2000s did lead to more births, we don’t agree with the back-of-the-envelope calculation presented by Perkins. We explain why below.

The headline number cited by Perkins comes from the results in Table 3, sample 4, where the reported impact is an increase in the probability of a birth to a woman aged 20-45 in a couple with low levels of education of 0.0130 percentage points. Given that the probability of a birth for such women was 0.089 before the reforms, the conclusion is that the reforms increased the probability of a birth to a woman aged 20-45 in a couple with low levels of education by 15%; this is equivalent to saying that the reforms increased the number of births to women aged 20-45 in a couple with low levels of education by 15%. This is the number that Perkins has used to reach his conclusion. But he has used the number wrongly in the following ways.

First, our research looked only at the number of babies being born in the few years shortly after the reforms. As we say (p254), “this means that we cannot fully distinguish whether an observed effect is due to changes in the total number of births or changes in timing”. (By “changes in timing”, we mean women having babies earlier than they otherwise would). One extreme would be that the 15% rise in births that we found might all represent additional children who would not have been born in the absence of the reforms; the other extreme is that they might all represent parents choosing to have children a little earlier than they would have done otherwise. In the latter case, the reforms would have had no impact at all on the number of children being born overall, but would only have changed the time profile of these births. We think it is highly likely that at least some of the change was in the timing of births and in the paper we present evidence that the reforms slightly reduced women’s age-at-first-birth. This means that the 15% is an upper bound on the true impact on the number of additional children being born.

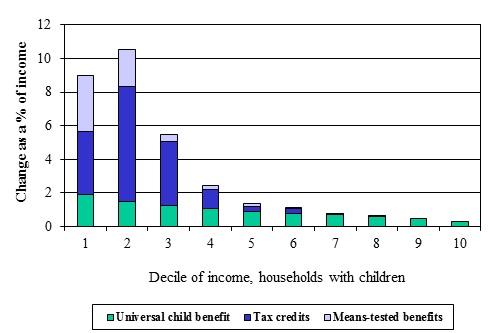

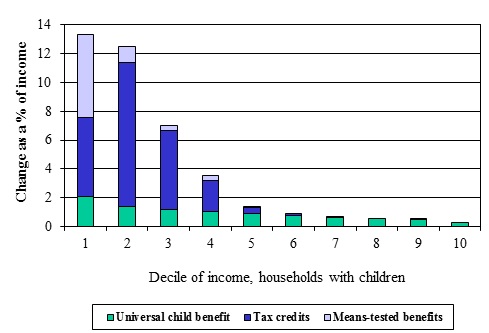

Second, Perkins conflates low-income households (which are the focus of our study) with workless households. We studied the effect of reforms implemented from 1999 to 2003 which increased child additions to in-work and out-of-work benefits, as well as substantially increasing the overall generosity of in-work benefits. As the figures below show (taken from our paper), the beneficiaries were to be found in the bottom two income decile groups, and, to a lesser extent, in the 3rd and 4th income decile groups. The figures also show that the largest single contribution to the increase in child-contingent benefits was the increased generosity of the Working Families’ Tax Credit compared to its predecessor, Family Credit, and this was a benefit that was paid only to families with at least one adult working 16 or more hours. So, it is not the case that our research found that the reforms increased births amongst workless or welfare-receiving families by 15%: instead, our research found that the reforms increased births amongst couples where both adults have relatively low levels of education by 15%, and where the majority of the additional support for families with children was conditional on having at least one adult in work.

Third, a clear finding from our research is that not all low-income families receiving additional government support responded to the increase in government support. In our research, we differentiated between lone mothers and women in couples because we thought that the impact of the reforms on fertility was likely to be different for the two groups; specifically, that it was likely to be stronger (more positive) for women in couples. As we described above, the majority of the increase in support in the period we studied came through more generous tax credits which were conditional on parents being in work. For lone mothers, the fact that the extra benefits in WFTC were contingent upon being work could actually have reduced incentives for lone mothers to have children (because the reforms meant that they would have had to have given up a greater amount of income had they stopped work to have children). However, for women in couples that were receiving WFTC and where the man worked, the way that tax credits were tapered away as the family’s earnings rise acted like a high marginal tax rate and was actually a disincentive for such women to work (provided their partner remained in work); this in turn would have lowered the cost – in term of foregone income – of taking time out of employment to have a child. And this distinction turns out to be important: we found that the reforms had no statistically significant impact on the number of births to lone mothers (sample 3, Table 3). Perkins’ calculation assumes the 15% figure applied to all family types: both adults living in couples and single adults living alone. However, we found that the overall impact of the reforms on births to all women aged 20-45 was smaller than our central result, at a 0.0055 ppt increase (and was statistically insignificant).

Fourth, and very pedantically, our research found that the reforms increased the number of births by 15% compared to their pre-reform level. This means that the number of additional births as a fraction of all post-reforms births (which is the calculation that Perkins performs) is actually 13% (=15/115), not 15%.

Our research highlights the fact that decisions about whether and when to have children are affected by material circumstances and incentives. It adds to a body of research that shows that the generosity of government support can have an impact on birth rates for some households. But it does not imply the scale of changes to the number of children born into workless families that Perkins has suggested.

Increase in child-contingent benefits

1998 – 2000

Couples, one child

Couples, two children

Source: Figure 1 of our paper, available from http://0-www.jstor.org.serlib0.essex.ac.uk/stable/pdf/41408911.pdf.

Professor Mike Brewer, University of Essex

Dr Anita Ratcliffe, University of Sheffield

Professor Sarah Smith, University of Bristol