Young people are heavily affected by downturns in the labour market, such as the most recent Great Recession and it has been shown that poor quality jobs and longer stints of unemployment can have long-lasting effects on their careers.

Our research shows that young adults who grew up in poorer and more disadvantaged households are the most vulnerable. During a recession these disadvantaged young adults are most likely to be unemployed or find themselves excluded from well-paying jobs, even if they have similar qualifications to their more advantaged peers.

Lessons from Germany

German data from 1984 to 2011 shows that family background does not really matter among people with similar qualifications when the local unemployment rate is low. As the labour market slackens, however, background begins to play more of a role and the disadvantaged are most likely to struggle to find a job and, even if they do, it’s likely to be low paid and temporary.

Family background is often found to be more important in the UK than in Germany, so it is likely that it would be the same story here. In the context of commitments across the political spectrum to reduce inequality and improve social mobility, these findings are important.

They show that sheer bad luck when entering the labour market matters more for young adults from already vulnerable backgrounds, and this could play a role in cementing inequality and disadvantage over several generations.

Social mobility and background

Growing up in a disadvantaged household affects education, but can also affect skills and the type of connections you have access to.

Even among young adults with the same qualifications, those who grew up with poorer or lower class parents may therefore seem less desirable to employers than their more advantaged peers. The degree to which this actually matters depends on the labour market conditions in which employers make their decisions.

This research shows that young adults aged 16 to 35 who are growing up in the 20% least advantaged households find it hardest to secure a good job. Background is not that important when there are enough jobs, but as jobs become scarce, the disadvantaged lose out more and are bumped down to jobs for which they are overqualified, that pay less, or even to unemployment.

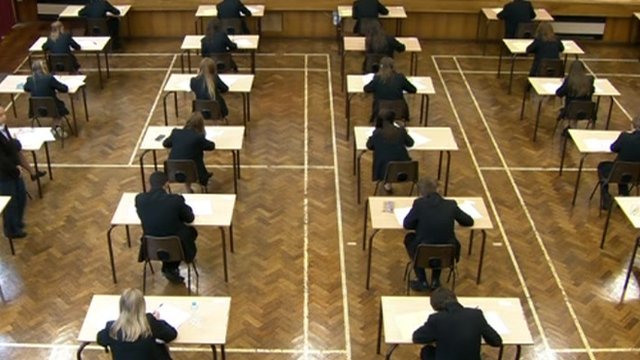

Education also makes a difference. As the unemployment rate increases, those with, at most, secondary-school qualifications are less likely to be employed at all or to work on permanent contracts.

A disadvantaged young adult in this group looking for work at an unemployment rate of 12% is 14 percentage points less likely to be employed and 15 percentage points more likely to work on a temporary rather than a permanent contract than if the unemployment rate was 5%.

For an average young adult with similar qualifications, this difference makes them 4% more likely to be unemployed and 2% more likely to work on a temporary contract.

Whilst having post-secondary qualifications improves a young person’s chance of getting a job, those who don’t have a job are most likely to come from a disadvantaged background.

Labour market forces can also affect wages. In Germany, a disadvantaged young adult who starts employment during an unemployment rate of 12% earns €0.79 less per hour than they would have had they started when the unemployment rate was 5%.

For an average person, this difference is only €0.30 and for the most advantaged it is a negligible €0.12. There is no reason to suspect this effect would disappear in the context of the UK.

Networks matter

These discrepancies by background could be linked to the type of job those from a disadvantaged background end up doing. As the unemployment rate increases, the disadvantaged become less likely than their more advantaged counterparts to find jobs that match their qualification levels. In a tough economic climate, the disadvantaged no longer manage to find appropriate jobs or jobs at all.

Having the right contacts does not seem to really matter in this context. Networks are less important in Germany in general however, so in the UK, knowing the right people may still matter. Despite the best efforts of successive UK Governments to tackle social inequality and mobility, it would appear that a child’s life chances are still largely determined by parental income and social standing.

The children of middle class parents may not be better qualified than their poorer classmates, but they enjoy many more advantages when it comes to finding well paid employment. Class based cultures and prejudices are deeply ingrained in British society and breaking down these barriers will need a multi pronged approach.

The lessons for policy

As far as policy is concerned, this research makes it clear that efforts to improve social mobility should not be limited to eradicating educational inequality. There needs also to be widespread commitment to help those from a disadvantaged household translate their educational success into a good job or career.

This could involve more investment in teacher training aimed at developing teaching strategies to reduce the attainment gap. Recent Ofsted reports have shown that schools do not have the skill set to provide the best careers advice. The National careers service could be given a much higher profile in driving the delivery of high quality careers advice to schools.

Consideration could also be given to the improvement of funding to area based careers services and to improved connections between employers and careers advisory service and work experience in schools could be re-focused to ensure it is more effective.