It’s a difficult time to be a young person in the UK. Fifteen-year-olds report lower levels of happiness and life satisfaction than their peers in almost all other developed nations (OECD, 2022). At the same time, they face a high-stakes examination system in which marginal differences in performance have considerable long-term consequences (Machin et al., 2020). The pressure to succeed academically remains unavoidable, even as concerns about young people’s wellbeing grow.

This pressure is also not evenly distributed. Persistent structural inequalities mean that the UK education system does not serve all pupils equally. Socio-economically disadvantaged pupils, on average, continue to underachieve compared to their more advantaged peers, despite decades of policy efforts to close attainment gaps (EPI, 2025). These disparities also intersect with minoritised ethnicities and institutional bias, compounding disadvantage for families who already lack the resources needed to navigate an increasingly competitive education system.

Teachers appear to be feeling the strain. In 2025, 89% of teachers considering leaving the state sector cited “stress and/or poor wellbeing” as a contributing factor, up from 84% in 2023 (DfE, 2025a). Parents, meanwhile, are responding to these pressures by investing in private tutoring (Cullinane & Montacute, 2023) and elective home education (DfE, 2024), options that remain inaccessible to many due to cost. The result is a widening gap between those who can afford additional support and those who cannot.

Policymakers are, however, taking action. Young people’s mental health has become a major policy priority, with the Secretary of State for Education calling for “a profound reform in what we value in our schools” so that wellbeing is prized as highly as academic attainment (Phillipson, 2024). Out-of-school settings have also returned to the policy limelight, with the DfE expressing interest in how enrichment and additional learning opportunities beyond the school day might improve all children’s health, socio-emotional development and educational outcomes (DFE, 2025b).

Yet one domain remains largely overlooked within the realm of out-of-school settings: initiatives organised by minoritised communities themselves to support both students and parents, also known as supplementary education. These schools, often run by volunteers and embedded in community spaces, provide cultural continuity and academic support at little or no cost. They represent a critical, under-researched resource that could help address both wellbeing and educational inequality.

In this blog, and against this contextual backdrop, we present key findings from exploratory research funded by the Young European Research Universities Network Researcher Mobility Awards. Drawing on combined expertise from both Belgium and the UK, the research sheds light on one form of out-of-school provision that remains vastly under-researched in the UK context and yet likely contributes to pupils’ wellbeing andacademic attainment: supplementary schools.

What is supplementary education and how many children attend?

Supplementary schools are educational initiatives organised by and for particular ethnic-cultural groups outside of the regular school day. They are often registered as charities, run mainly by volunteers, and held in religious or community centres or mainstream school buildings. Unlike private tuition – which normally comprises lessons delivered to one or a very small group of children to support them in specific academic subjects – supplementary schools usually serve anywhere between 10 to 300 pupils and have two broad aims: (1) to develop the minoritised ethnic child’s cultural identity; and (2) to promote the achievement of the minoritised ethnic child in their mainstream schooling through additional instruction. Importantly, most supplementary schools do not charge high tuition fees, and some even operate entirely free of charge, making them accessible to families with limited financial resources (Simon, 2018; Steenwegen, 2022; Strand, 2007).

International research highlights both the widespread attendance of these schools and their significant role in the lives of minoritised youth and their communities (Coudenys, 2025; Simon, 2018). These studies underscore that supplementary schools are not marginal but rather central spaces for cultural continuity and educational support across various ethnic-cultural groups. However, in the UK, there are no nation-wide administrative or survey datasets containing information about supplementary schools or the pupils who attend them. Nonetheless, proxy data indicates that attendance may be increasing and is concentrated among young people with a migration background.

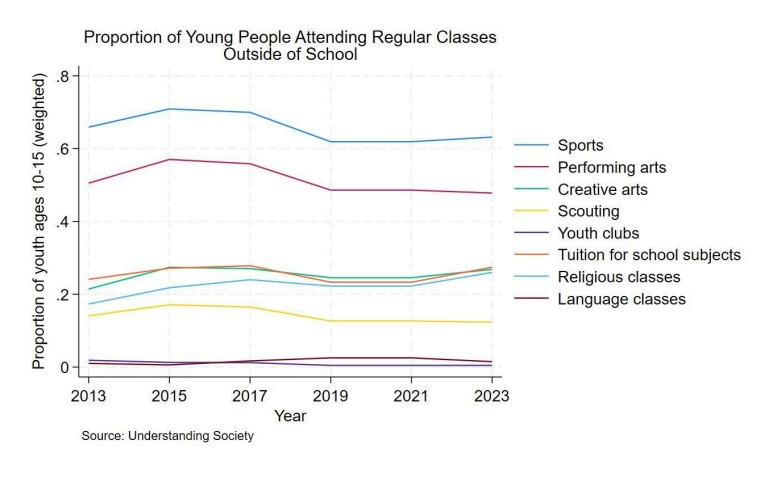

Graph 1: Trends in the proportion of young people attending regular classes outside of school, 2013- 2023.

Graph 1 shows trends in the proportion of young people in the UK attending different types of regular classes outside of school using data from the Understanding Society panel cohort survey (n=15,727).

The graph shows that more than half of 10 to 15 year olds in the UK attend regular sports classes, around half performance arts (music, drama or dance), and more than one in five religious classes, creative arts or tuition for school subjects. The years shown on the x-axis represent the middle year of a two-and-a-half year data collection period for each wave, and as such the results in 2019 and 2021 likely include a negative Covid effect. The most recent data shows marked increases in both religious classes and tuition for school subjects.

Supplementary schools are not represented by a unique category in these Understanding Society data, though are most likely to overlap with language classes, religious classes and tuition for school subjects. It is noteworthy that religious classes and tuition for school subjects are the two categories showing the most marked increases in attendance in the most recent wave in Graph 1.

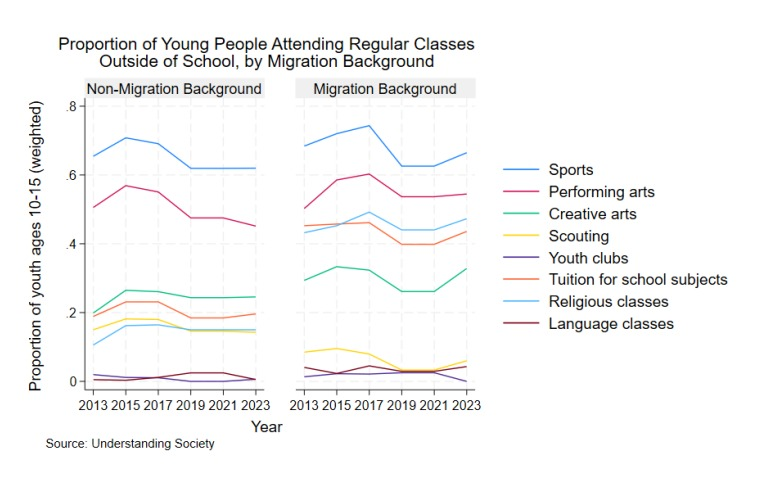

Graph 2: Trends in the proportion of young people attending regular classes outside of school by migration background, 2013-2023.

Graph 2, meanwhile, shows the same data as Graph 1 but this time with the sample split by migration background. We define young people with a migration background as those with a reported ethnicity which is not English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or Irish.

The most prominent differences between the two panels in Graph 2 are among religious classes and tuition for school subjects, which are noticeably higher among young people with a migration background. The proportions are higher than those found in the Belgium context, where 17% of surveyed ethnic minority pupils attend a supplementary school (Coudenys et al., 2025). They are also higher than existing UK estimates, where between 18 and 28 per cent of pupils from migrant and ethnic minority backgrounds were estimated to be in contact with supplementary schools (DCSF, 2009). This is unsurprising given that, like other UK surveys, the question asked by Understanding Society is not specific enough to formally conclude the equivalence with supplementary schools in the UK. This is one area that we hope to probe in our future research.

The fact that supplementary school attendance is likely much higher among pupils with a migration background in the UK is also noteworthy given that, unlike in many other nations, a large proportion of ethnic minority pupils in England do better than their White British peers in examinations taken at age 16 (Burn et al., 2024). It is possible that supplementary schools explain part of this difference.

What do we already know about supplementary schools and their potential impact?

After a small burst of policy and research around UK supplementary schools in the early 2000s, interest has reduced considerably over the last twenty years, and the lack of existing data about the initiatives means that their spread and impact is very hard to measure.

One of the most informative studies is a survey conducted among 722 pupils in 63 supplementary schools around 2007 (Strand, 2007). This study found that pupils in supplementary schools were substantially more disadvantaged than the UK as a whole according to a measure of the number of books reported in the pupils’ family homes. It also found that the pupils attending supplementary schools held more positive attitudes towards their supplementary compared to their mainstream schools, and that these pupils received instruction for more than just a heritage culture or language; general educational attainment, and in particular with English or mathematics, was the most commonly cited reason to attend.

More recently, UK think tank The Institute for Public Policy Research released a report (IPPR, 2015) arguing for greater collaboration between mainstream and supplementary schools, which they estimated to number between 3,000 and 5,000 in England alone. They emphasise supplementary schools’ successes with personalised learning, opportunities for young people to explore complex questions of identity, and positive parental and community relationships; all areas that are currently rising to the top of the UK’s list of challenges facing the mainstream education system. They also note that much of the funding the schools receive from sources other than parents, including local councils, had been scaled back in recent years.

Alongside these reports, there is a rich body of ethnographic, qualitative case studies across the UK that examine supplementary schools and other educational initiatives organised by ethnic-cultural groups (e.g., Andrews, 2014; Archer et al., 2009; Burman & Miles, 2020). These studies provide invaluable insights into how these initiatives are organised, who participates, and for what purposes. They offer a wealth of knowledge about the communities involved and the social, cultural, and educational roles these schools play. This work is crucial for understanding the lived realities behind the numbers.

Overall, however, there remain substantial limitations to the existing literature on supplementary schools. To the best of our knowledge, there exist no official records of surveys of supplementary schools, no large-scale quantitative evaluations, and no previous research at a national level. Although a handful of studies try to estimate the impact of the schools, no true causal estimates have been attempted due to the difficulties of implementing either experimental or quasi-experimental research designs. Instead, multivariable regression appears to be the most commonly-taken approach (e.g. Papastergiou and Sanoudaki, 2021), however in these analyses it remains likely that unobservable factors (such as parents’ more general engagement in their children’s education) drive supplementary school attendance as well as higher test scores. Causal estimates of supplementary school attendance is therefore another facet we hope to be able to approach in our future research.

How are supplementary schools operating in the current UK context?

Given these gaps in the evidence base, we set out in this project to understand what is actually known about supplementary schools today. While qualitative case studies provide rich insights into how these initiatives operate and the roles they play in their communities, there is very little systematic information about their current scale or organisation. This lack of data makes it difficult to assess their potential contribution to addressing educational inequality and wellbeing challenges in the UK.

To begin addressing this, we launched an exploratory research focused on one region where supplementary schools are thought to be most concentrated: London. Our aim was not to produce definitive estimates, but rather to map what information is currently available and to identify possibilities for future research. Below we describe the steps we took in this limited research project and the results of these various stages of the research.

We started out with sending Freedom of Information requests to every borough in London, where the density of supplementary schools is generally accepted to be considerably higher than other parts of the UK (Strand, 2007). We received responses from 30 out of 32 boroughs. Through this first step, we first found that very few boroughs in London had any oversight of the supplementary education provision in their area, with only nine (28%) boroughs able to provide any information about existing schools, current or previous grants, or organisations or individuals with some oversight. Of those only Islington and Camden could provide a full picture of supplementary schools in their area. The borough of Camden kindly provided us with additional information upon request. Below we dive a little deeper into this information.

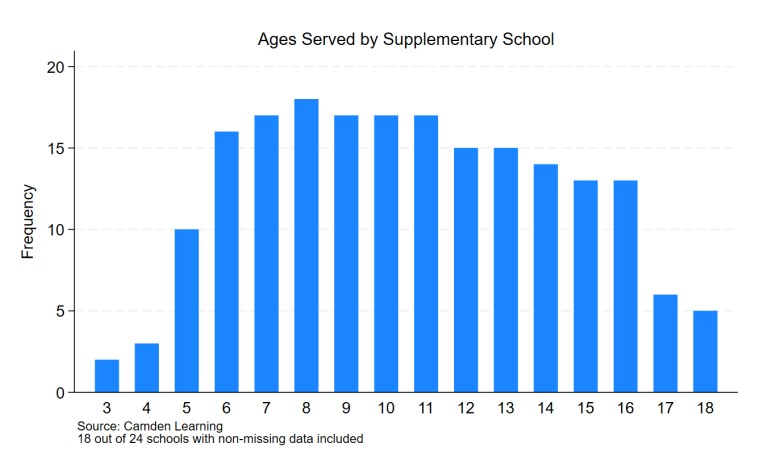

Graph 3: Ages served by supplementary schools in Camden

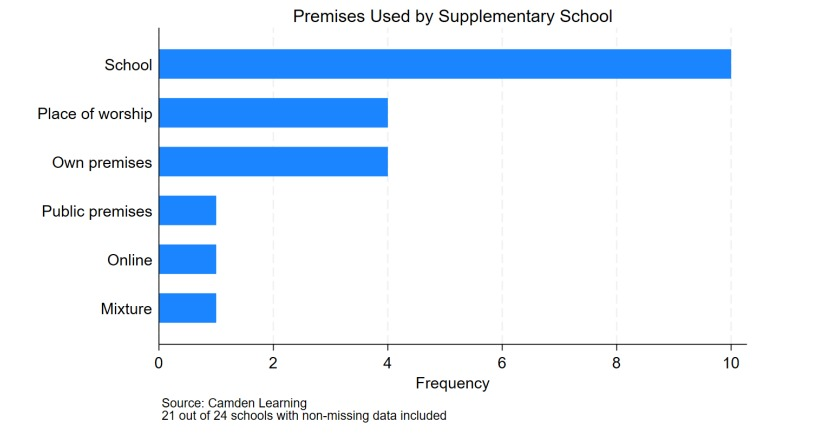

Graph 4: Premises used by supplementary schools in Camden

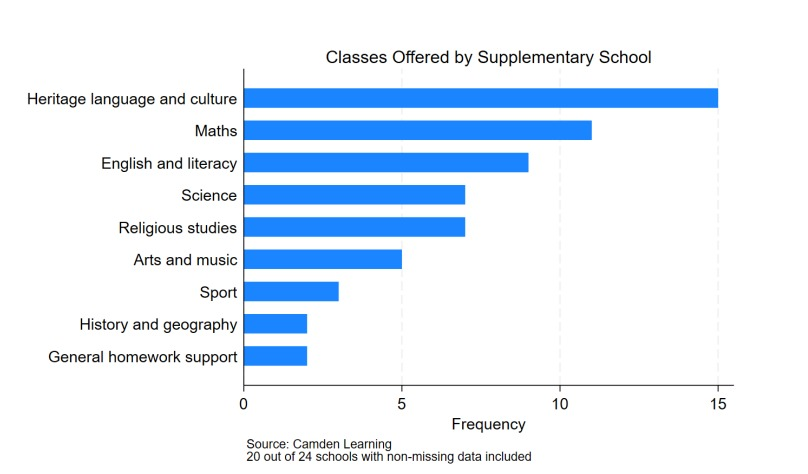

Graph 5: Classes offered by supplementary schools in Camden

Graphs 3, 4 and 5 show the characteristics of supplementary schools in the London Borough of Camden, which collects data on all of their supplementary schools.

Graph 3 shows that supplementary schools have fairly consistent provision for children of compulsory full-time schooling ages, between five and 16, whilst Graph 4 shows that most supplementary schools hire school premises to use for their classes. In Graph 5, we learn that three quarters of supplementary schools offer heritage language and culture classes while over half offer maths and English support. In this way, supplementary schools can be seen as largely working in tandem to the aims of mainstream schools. Indeed, it has been documented elsewhere that many pupils take GCSEs in their heritage language but are entered for the exam at their mainstream setting (Young, 2024), which is just one example of the ways in which supplementary schools work in partnership with mainstream settings.

While Camden’s data offered useful insights into the characteristics of supplementary schools – such as their age range, use of mainstream premises, and focus on heritage language and culture alongside maths and English – it still left many questions unanswered. To deepen our understanding, we explored additional avenues for a second phase of information gathering: conversations with experts in the field, school visits, and the development of a survey.

Early in the second phase, we spoke to representatives from funding organisations and charities such as John Lyon’s Charity and Young People’s Foundation (YPF), who were invaluable in helping us understand the broader landscape of supplementary education. These discussions revealed two critical insights. First, many organisations concerned with supplementary education mainly focus on funding, which seems to be a considerable obstacle; while some funding streams exist for supplementary schools, accessing them requires significant effort and administrative capacity, meaning many schools rely on indirect funding through larger organisations. Second, safeguarding is another major area of work for and around supplementary schools, with growing attention to compliance and child protection. We also learned about an emerging movement toward establishing a quality mark for supplementary schools, aimed at recognising and supporting good practice across the sector.

Building on this, we decided to go beyond documents and data and spend time on the ground. We were fortunate enough to visit four schools in London to observe classes and speak to initiators. These schools served the Chinese community, Afghan community, and Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) children attending local schools. Three were held on Saturday mornings in mainstream school premises or on weekday evenings in the charity’s own premises. Many of the teachers in the Saturday schools were qualified and often taught in mainstream schools during the week. The weekday evening classes, meanwhile, were staffed by ex-pupils who came back to volunteer their time for their home community. These visits were invaluable. They allowed us to see the diversity of provision first-hand, from Saturday schools run by qualified teachers in mainstream classrooms to weekday homework clubs where volunteers, often former pupils, support children for free. In one case, a volunteer explained that she returned to help because she herself had once received support from the same school, a powerful example of communities showing up for each other.

These conversations also helped shape further research tools. While visiting these schools, we moved into a next research phase in which we aimed at developing a survey intended to gather additional information about who funds supplementary schools, when and where they are held, broadly who attends, and what provision they offer. We piloted this survey during our visits and asked teachers and organisers to offer feedback and suggest questions they felt were important. One school, for example, demonstrated how they work closely with parents to ensure pupils with special educational needs receive tailored help, highlighting the depth of care and commitment within these community-led initiatives. Their input led us to include topics such as how schools support pupils with special educational needs.

Seeing these schools in action also reinforced what earlier studies have documented: supplementary education is not just about academic support, it is about identity, belonging, and mutual care. These experiences remind us that behind every statistic lies a vibrant network of relationships and aspirations.

In collaboration with the London Borough of Camden and Young Camden, we were then able to distribute our survey to all supplementary schools in the borough. Unfortunately, the response rate was very low (8%), meaning that it is not possible to analyse the responses systematically. Nonetheless, some comments were illuminating. For example, when asked about the vision or purpose for the school, one initiator stated: “To be a safe and inspiring platform where young people can grow in confidence, feel a deep sense of belonging, and connect meaningfully with others through the shared language and cultural heritage of the… community.”

Funding was cited as the biggest challenge currently facing supplementary schools in Camden, echoing what we learned from our earlier conversations with charities and funders, and the initiators of the schools we visited.

What next for this project?

Because there is so little large-scale research on supplementary education in the UK, even this exploratory phase revealed a wealth of possibilities for deepening our understanding. From mapping funding streams and documenting the challenges schools face, to evaluating their impact on academic attainment and wellbeing, and co-producing research that responds to the needs of schools on the ground, we found an enormous scope for future work. Considering that there is very limited research out there, and that policymakers are beginning to turn their attention to out-of-school spaces, this is a critical moment to build an evidence base that can inform decisions and support equitable provision.

Our visits and conversations showed that supplementary schools are not only educational spaces but also hubs of community care, identity, and resilience. Capturing this complexity requires research that combines robust quantitative evidence with the rich qualitative insights already available. Doing so will not only illuminate the role these schools play in addressing educational inequalities but also highlight their contribution to social cohesion and cultural sustainability.

With the support of the YERUN Network we were able to explore initial avenues of research on supplementary education in the UK, but what we mostly found is how much need there is for robust research and a much better and deeper understanding of this realm of out-of-school educational spaces. Therefore our next steps for this project include convening a round table with school initiators, youth organisation, and larger funders, to begin co-producing a larger research funding proposal. Our aim is to document the spread and scope of supplementary schools in the UK and to explore the perceived benefits of attending, both from pupils’ and parents’ perspectives. We also hope to provide the first causal evaluation of the effects of supplementary school attendance on mainstream academic attainment and pupil wellbeing, addressing a critical gap in the evidence base.

If you are interested in getting involved with the future of this research project, please do not hesitate to get in touch with either Hettie (at h.burn@ucl.ac.uk) or Blansefloer (at blansefloer.coudenys@uantwerpen.be).

We are immensely grateful to the following individuals and organisations for supporting us with this exploratory research: Young European Research Universities Network, Camden Learning, Young Ealing Foundation, Securing Success Harrow, Young Westminster Foundation, John Lyon’s Charity, Young People’s Foundation Trust, Minority Matters, Qing Hua School, Mashal School, Stag Lane School, Albanian School ‘Kosova’, Civitas Schools.

References

Andrews, K. (2014). Resisting racism: The Black supplementary school movement. Alternative education and community engagement: Making education a priority. O. Clennon. London, Palgrave Macmillan: 56-73.

Archer, L., et al. (2009). “‘Boring and stressful’ or ‘ideal’ learning spaces? Pupils’ constructions of teaching and learning in Chinese supplementary schools.” Research Papers in Education 24(4): 477-497.

Burman, E. and S. Miles (2020). “Deconstructing supplementary education: from the pedagogy of the supplement to the unsettling of the mainstream.” Educational Review 72(1): 3-22.

Burn, H., Fumagalli, L., Rabe, B. (2024). Stereotyping and ethnicity gaps in teacher assigned grades. Labour Economics, 89.

Coudenys, B., Dekeyser, G., Clycq, N., and Agirdag, O. (2025). The impact of part-time community education on the academic achievement of minoritised pupils: evidence from Flanders. Oxford Review of Education.

Cullinane, C. and Montacute, R. (2023). Tutoring – the new landscape: Recent trends in private and school-based tutoring. The Sutton Trust.

DCSF (2009). Impact of supplementary schools on pupils’ attainment: an investigation into what factors contribute to educational improvements. Department fort Children, Schools and Families, Research Report DCSF-RR210.

DFE (2024). Autumn term 2024/25: Elective home education. Department for Education Explore education statistics.

DFE (2025a). Working lives of teachers and leaders – wave 4: Summary report. Department for Education.

DFE (2025b). Areas of Research Interest. Department for Education.

EPI (2025). Breaking down the gap: The role of school absence and pupil characteristics. Education Policy Institute.

IPPR (2015). Saturdays for success: How supplementary education can support pupils from all backgrounds to flourish. Institute for Public Policy Research.

Machin, S., McNally, S., and Ruiz-Valenzuela, J. (2020). Entry through the narrow door: The costs of just failing high stakes exams. Journal of Public Economics, 190. Article 104224.

OECD (2022). United Kingdom: Student performance. OECD Education GPS.

Papastergiou, A. and Sanoudaki, E. (2021). Language skills in Greek-English bilingual children attending Greek supplementary schools in England. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25:8.

Phillipson, B. (2024). Speech to the Confederation of School Trusts. Department for Education.

Simon, A. (2018). Supplementary Schools and Ethnic Minority Communities: A Social Positioning Perspective.

Steenwegen, J., et al. (2022). “How and why minoritised communities self-organise education: a review study.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education: 1-19.

Strand, S. (2007). Surveying the views of pupils attending supplementary schools in England. Educational Research, 49:1, 1-19.

Young, S. (2024). The Struggle for Professional Recognition by Polish Complementary Schools When Preparing Students for the GCSE Polish Exam During the 2020 COVID-19 Exam Period in England. British Journal of Educational Studies, 73:3.